#May68: from Prague to Mexico City

Sol Henaro and Zbyněk Baladrán

In this conversation, Sol Henaro, curator of the Arkheia Archive and Research Center at MUAC and Zbyněk Baladrán, author, artist, curator and co-founder of Display in Prague, engage in a conversation about the aesthetic and political legacies of May 68 in Mexico and the Czech Republic, looking into historical perspectives that can enable oblique political trajectories while reading their impact in contemporary right-wing populism and the neoliberal abstraction of the world.

Infrasonica

When we first conceived of this conversation, May 68 emerged as a sort of epistemic detonator, which would allow us to read our contemporary global condition in a world where new political horizons seem lost.

Last year at MUAC, Sol and Amanda de la Garza curated a show called “Grafica of 68: Imagenes Rotundas”, a project that explored the visual repertoire of the 1968 movements in Mexico through its social and artistic articulations on its 50th anniversary. Zbyněk, through your projects Building Archive and History is Possible, you have worked on tracing the political narratives of real defeat and the speculative success of socialism in the Czech Republic, as well as the wider context of Eastern Europe. I find it fascinating how these local narratives both differ from the mainstream Western version of the French 68, while also differing from each other. In the case of Mexico, the movement represented a struggle against a capital oriented dictatorship. In Prague, it was more of an effort to humanize real socialism. Could you each begin by expanding on how the above projects have, 50 years later, helped you to gain perspective regarding these political and aesthetic movements?

Zbyněk Baladrán

It is even more complicated with the year 68 in Czechoslovakia. You are right that what is called Prague Spring 68 was the culmination of the effort to humanize real socialism, respectively seeking greater democratization within the socialist state. Censorship ceased to work, people could travel freely, and they were thinking up plans for a third way in the organization of the modern state. All this ended with the Warsaw Pact troops occupation on August 21st. It was a shock that neither the Communist Party nor the population recovered from. The new Communist Party leadership offered something like a new social contract. In short: After the Communist Party had cleared out all the people who did not approve of the occupation, it took the population's political life and instead offered them a socialist version of consumerism. I apologize for the long introduction, but I wanted to highlight what I believe was the moment when the current Czech anti-Communist sentiment was born. The current neoliberal state propaganda has successfully concealed the narrative of emerging democratic socialism and overlaid it with a narrative of military occupation: The villains of the East are stomping us in the backyard.

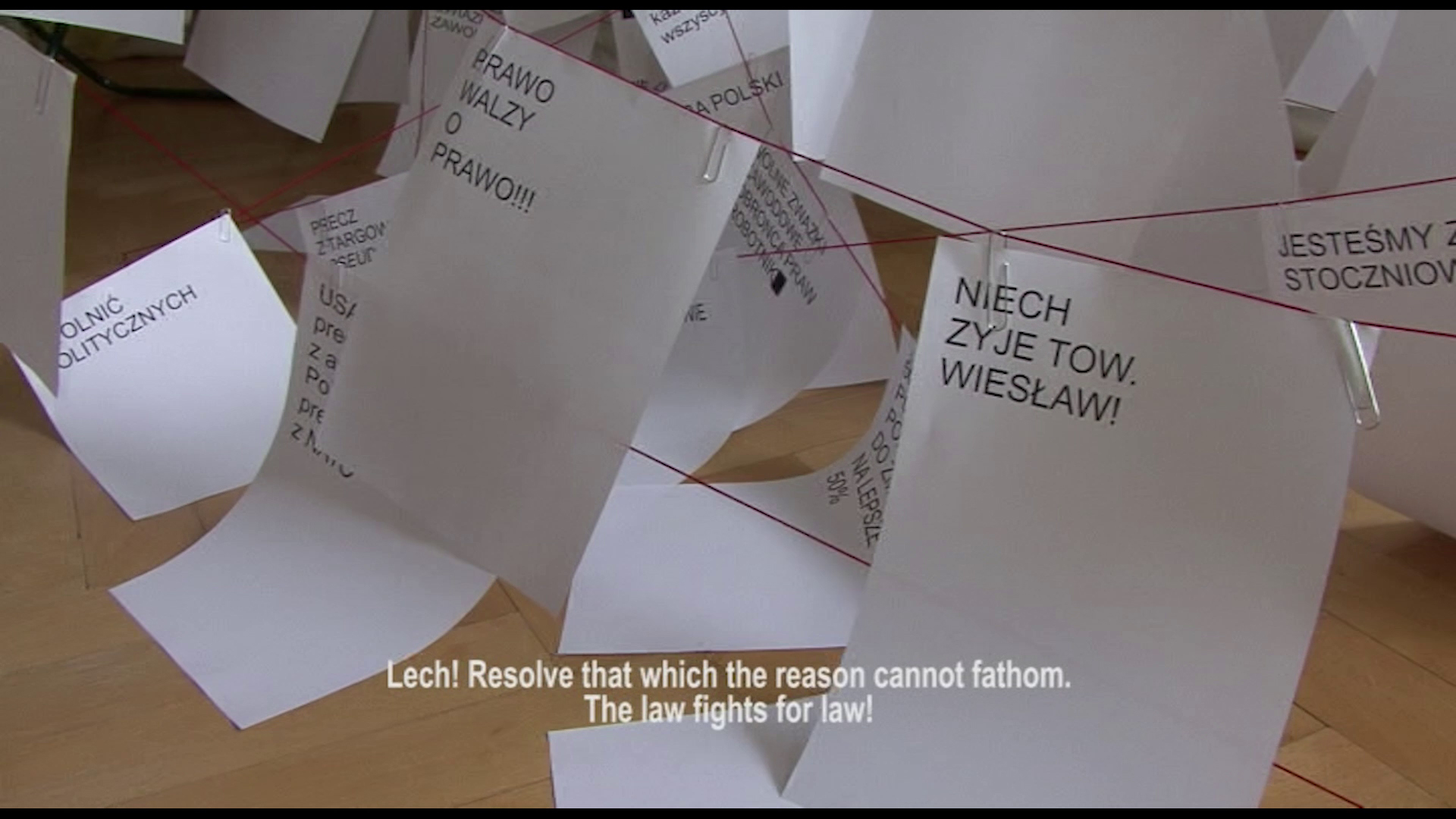

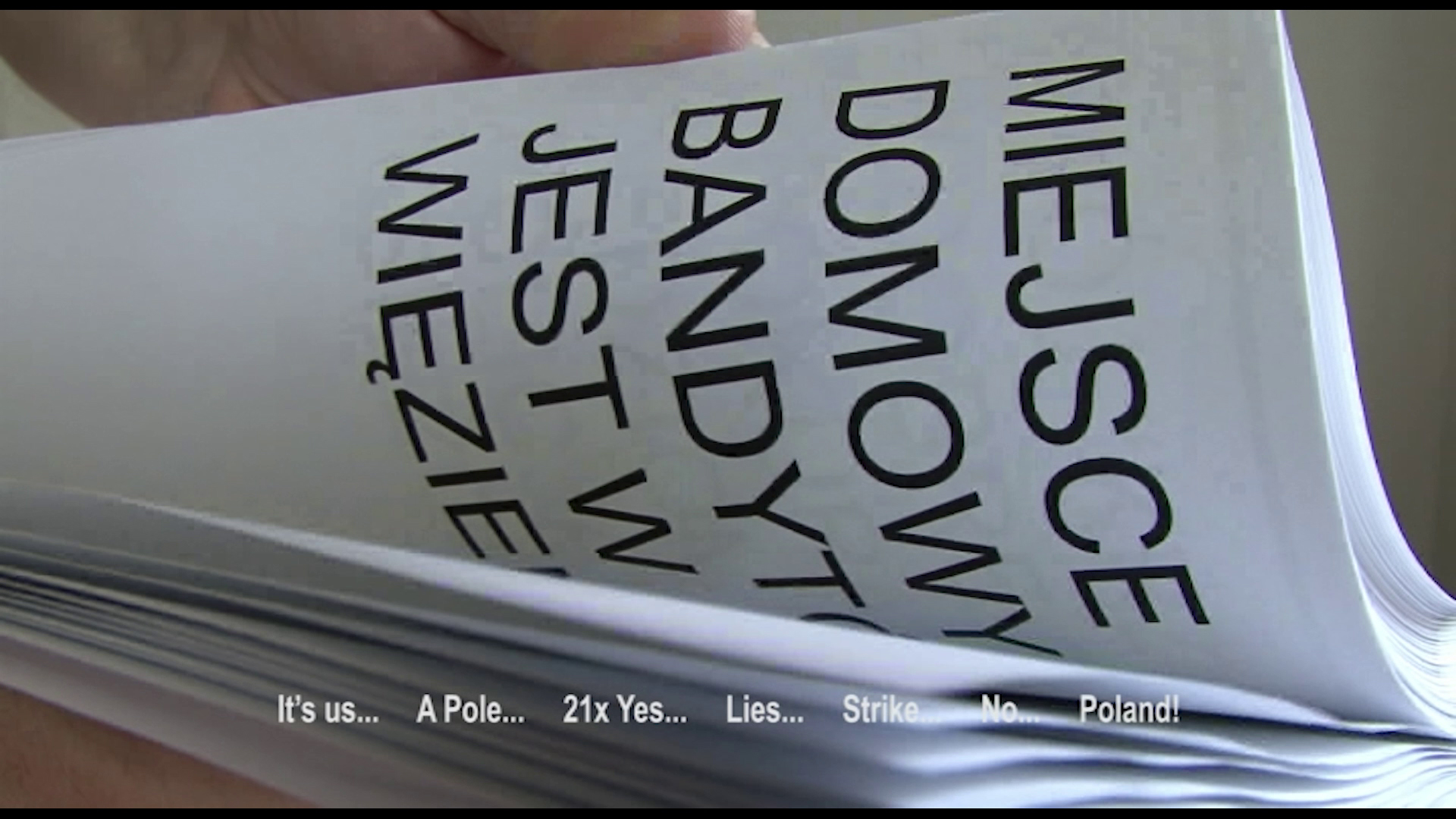

The video Building Archive helped me realize this. I studied strike and protest movements in Poland at that time and realized that the year 68 meant something different in each country. Poland was one of the countries that occupied us, but I was surprised to find that there were also protest events. Thanks to this, I focused more on what preceded the occupation, on the inspirational part of Czechoslovak history.

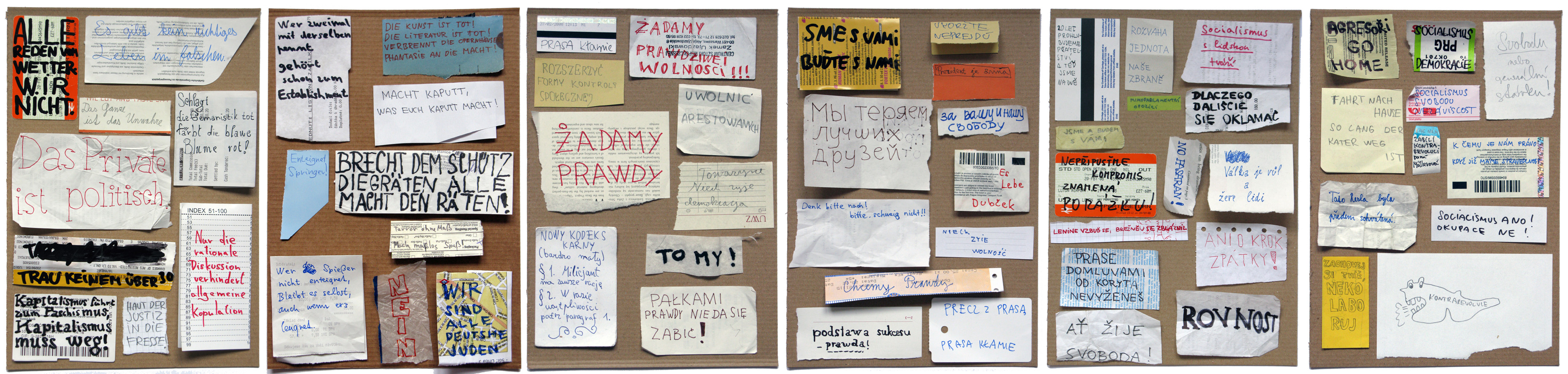

Atlas of protest slogans, 12 collages, paper A4, 2008. Courtesy of Zbyněk Baladrán.

Sol Henaro

Your observation about how these micro-narratives break into the milestone of the French 68 feels very important because, as we know, 68 coincided with diverse mobilizations in other contexts and, well, each one has its particularities and contexts that signify them It’s also interesting to think of a kind of “simultaneity of conflicts” where the youth factor played a fundamental role within them. This brings me to the work of the Argentine photographer Marcelo Brodsky, who has worked with diverse photographic documents of mobilizations that took place across different countries in 1968.

In the case of Mexico, for the commemoration of the events of the 1968 student movement, it proved impossible to think of these events without also considering recent vile and traumatic events such as the forced disappearance of the 43 normalists of the Escuela Normal Rural Isidro Burgo in Iguala, Guerrero in 2014, an occurrence that sadly received international visibility for its severity. We live in Mexico, a country where mobilizations are as constant as the exercises of power about who can raise a critical voice towards the State, or to any perspective that it involves. The case of Ayotzinapa was so brutal of an occurrence that it was difficult not to make a comparison with the killing of the students in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas de Tlatelolco on the 2nd of October in 1968. In both cases, Tlatelolco and Ayotzinapa, the role of the State was to give orders to proceed, cover-up, and hide evidence or block the investigations of third parties, which activated an alarm in many of us. What I'd like to highlight with this is that the commemoration obliged us to ask ourselves where we are today; what has changed? How can brutal events like 68 continue to happen today without firm and direct judicial response? What are we really talking about when we speak of memory?

Infrasonica

Sol, your final question about memory is key to understanding a problematic where time-space and political events are entangled. May 68 was the interruption of Time as History – as Zbynek assertively pointed out with the Building Archive project based on his research in Poland. However, one thing that shocks me when thinking about this is the fact that the violent nature of the State apparatus still operates in very similar ways, and after 50 years, we wonder what has changed?

If we could draw, based upon your comparative experiences, a characterization of the state and its complicity with neoliberalism, what do you think has changed in terms of its local manifestations in Mexico and the Czech Republic? And how have visual strategies of resistance and sabotage also mutated in terms of this relation?

Zbyněk Baladrán

I feel that the modern organized state under socialism was no so much different from that of today. It was based on the same technocratic patterns, except that property is now distributed more asymmetrically and more unfairly. In the Czech Republic, as in the entire Central European region, it is international capital and its corporations where almost all profits are paid. I would describe it as a kind of colonial vassalism within the wider Western world. Year 68 in Czechoslovakia culminated in a more participatory and open way of governance. The Communist Party almost lost its sovereign power. Compared to today, society is massively vertically reorganized on a wealth basis, i.e. in access to capital and resources. I remember how in the late 1980s it produced a smile when someone coveted money and success. The socialist man thought differently, he was not so heterotrophically individualistic oriented (of course, probably a little exaggerated, but what was natural was perceived differently in the socialist regime than what is natural today).

The visual strategies of resistance and sabotage are similar to those of fifty years ago. In Mexico, it's probably different, but in a country organized as ours is, radical strategies are hard to find. Artists and intellectuals are very well adapted to new circumstances, and radical criticism is a marginal issue without much influence. Certainly, it is related to the fact that it is difficult to imagine a different type of system than the one we have now, and only really as criticism as a correction of the existing system.

In general, everything within the limits of the law, but in the former repressive regime, they relied more on otherness and metaphor.

Building Archive, 2008, SD video, 6"56", in Polish with English subtitles (video still). Courtesy of Zbyněk Baladrán.

Sol Henaro

That reminds me of a Marcelo Exposito text that, in turn, pointed to Benjamin’s ideas related to memory and “the blow”, which materialist historians should give to stop the inertia and critically read the past from the present. We live as constellations of mobilizations, struggles that interconnect in different fashions… When you examine the protests in Mexico, or the collective swarm of reclamation in relation to the disappearance of the 43 students in Ayotzinapa, or the mobilizations against the hundreds of femicides, we observe the rage and also the reverberation, appropriation, and actualization of visual strategies of activism in diverse contexts. We also think about the Siluetazo in Argentina as a strategy, which has spread and been updated in different contexts. It’s complex to summarize the political system in Mexico, beginning with the party that was in power for 71 years (until 2000), for the systemic corruption or for the abuses of human rights, which unfortunately have not ceased to exist, and that which, as long as they continue to multiply, will continue to provoke mobilizations.

Finally, the question that, terribly, we cannot stop examining is: Are we normalizing violence or are we resisting it with multiple actions? Definitively opposing the second and in this sense, and also from artistic practice, those productions with certain positioning remain from the scope of visualities. I’d like to bring to attention the case of the #restauradorasconglitter (restores with glitter), a group of restorers who politicize their work to demand the stopping of the erasure of paintings, graffiti, and other visual residues from the passage of the protest against femicides on the monument to independence in Mexico City. Their slogans, #LaVidaTambienEsPatrimonio (Life is also patrimony) and #PrimeroLasMujeresLuegoLasParedes (Women first then walls) have begun an important debate more than the fact that they have integrated modern tools to their cause, such as social networks or the use of drones and 3D scanners to try to “capture”, let’s say, the visual DNA of the collective anonymous that is the mobilization… I read Initiatives like #restauradorasconglitter as “blows” to the inertia.

Building Archive, 2008, SD video, 6"56", in Polish with English subtitles (video still). Courtesy of Zbyněk Baladrán.

Zbyněk Baladrán

In the Czech Republic on the way to the neoliberal regime, the perception of what is private property and what represents the state has radically changed. Few perceive violence monopolized by the state as a type of repression that should be fought or criticized. The most striking is the criminalization of anarchists and activists squatting empty buildings in which they mainly create an alternative cultural program. The state, by sending heavy rioters into squats, became the primary protector of private property against anyone who would try to challenge it. In general, the anarchists' behavior is perceived as questioning the status quo and all the freedoms of which private ownership is the flagship in this regime. The conquest of such places by police or court hearings occupies virtual TV and Internet space for a while to leave the arrested activists in prison for a few months without noticing the media. Then Visual Protest Strategies usually move to the Internet, where their reach may be higher, but all the more toothless.